It feels as though we’ve barely absorbed the rapid development and adoption of generative AI technologies such as large language models (LLMs) before the next phenomenon is already upon us, namely agentic AI. Standalone LLMs can be thought of as “chatbots in a sandbox”, the sandbox being a metaphor for a safe and contained play space with limited interaction with the world beyond. In contrast, the vision of agentic AI is a near (or already here?) future in which LLMs are the underlying engines for complex systems that have access to rich external resources such as consumer apps and services, social media, banking and payment systems — in principle, anything you can reach on the Internet. A dream of the AI industry for decades, the “agent” of agentic AI is an intelligent personal assistant that knows your goals and preferences and that you trust to act on your behalf in the real world, much as you might a human assistant.

For example, in service of arranging travel plans, my personal agentic AI assistant would know my preferences (both professional and recreational) for flights and airlines, lodging, car rentals, dining, and activities. It would know my calendar and thus be able to schedule around other commitments. It would know my frequent-flier numbers and hospitality accounts and be able to book and pay for itineraries on my behalf. Most importantly, it would not simply automate these tasks but do so intelligently and intuitively, making “obvious” decisions unilaterally and quietly but being sure to check in with me whenever ambiguity or nuance arises (such as whether those theater tickets on a business trip to New York should be charged to my personal or work credit card).

To AI insiders, the progression from generative to agentic AI is exciting but also natural. In just a few years, we have gone from impressive but glorified chatbots with myriad identifiable shortcomings to feature-rich systems exhibiting human-like capabilities not only in language and image generation but in coding, mathematical reasoning, optimization, workflow planning, and many other areas. The increased skill set and reliability of core LLMs has naturally caused the industry to move “up the stack”, to a world in which the LLM itself fades into the background and becomes a new kind of intelligent operating system upon which all manner of powerful functionality can be built. In the same way that your PC or Mac seamlessly handles many details that the vast majority of users don’t (want to) know about — like exactly how and where on your hard drive to store and find files, the networking details of connecting to remote web servers, and other fine-grained operating-system details — agentic systems strive to abstract away the messy and tedious details of many higher-level tasks that, today, we all perform ourselves.

But while the overarching vision of agentic AI is already relatively clear, there are some fundamental scientific and technical questions about the technology whose answers — or even proper formulation — are uncertain (but interesting!). We’ll explore some of them here.

What language will agents speak?

The history of computing technology features a steady march toward systems and devices that are ever more friendly, accessible, and intuitive to human users. Examples include the gradual displacement of clunky teletype monitors and obscure command-line incantations by graphical user interfaces with desktop and folder metaphors, and the evolution from low-level networked file transfer protocols to the seamless ease of the web. And generative AI itself has also made previously specialized tasks like coding accessible to a much broader base of users. In other words, modern technology is human-centric, designed for use and consumption by ordinary people with little or no specialized training.

But now these same technologies and systems will also need to be navigated by agentic AI, and as adept as LLMs are with human language, it may not be their most natural mode of communication and understanding. Thus, a parallel migration to the native language of generative AI may be coming.

What is that native language? When generative AI consumes a piece of content — whether it be a user prompt, a document, or an image — it translates it into an internal representation that is more convenient for subsequent processing and manipulation. There are many examples in biology of such internal representations. For instance, in our own visual systems, it has been known for some time that certain types of inputs (such as facial images) cause specific cells in our brains to respond (a phenomenon known as neuronal selectivity). Thus, an entire category of important images elicits similar neural behaviors.

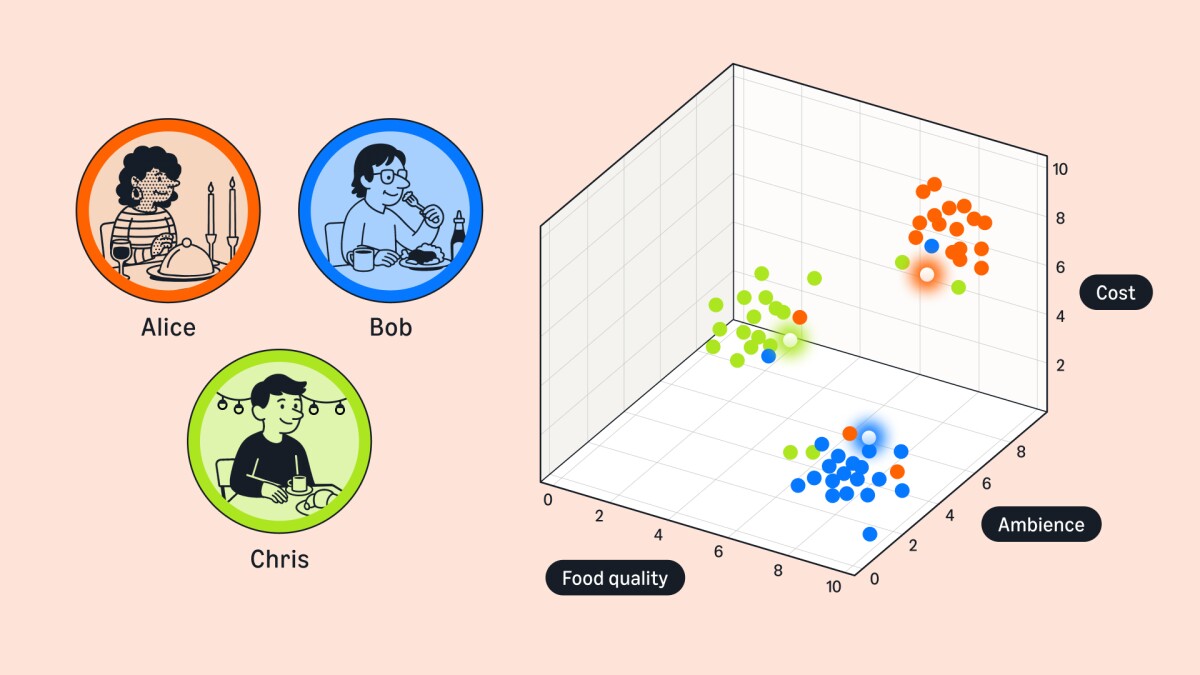

In a similar vein, the neural networks underlying modern AI typically translate any input into what is known as an embedding space, which can be thought of as a physical map in which items with similar meanings are placed near each other, and those with unrelated meanings are placed far apart. For example, in an image-embedding space, two photos of different families would be nearer to each other than either would be to a landscape. In a language-embedding space, two romance novels would be nearer to each other than to a car owner’s manual. And hybrid or multimodal embedding spaces would place images of cars near their owner manuals.

Embeddings are an abstraction that provides great power and generality, in the form of the ability to represent not the literal original content (like a long sequence of words) but something closer to its underlying meaning. The price for this abstraction is loss of detail and information. For instance, the embedding of this entire article would place it in close proximity to similar content (for instance, general-audience science prose) but would not contain enough information to re-create the article verbatim. The lossy nature of embeddings has implications we shall return to shortly.

Embeddings are learned from the massive amount of information on the Internet and elsewhere about implicit correspondences. Even aliens landing on earth who could read English but knew nothing else about the world would quickly realize that “doctor” and “hospital” are closely related because of their frequent proximity in text, even if they had no idea what these words actually signified. Furthermore, not only do embeddings permit generative AI to understand existing content, but they allow it to generate new content. When we ask for a picture of a squirrel on a snowboard in the style of Andy Warhol, it is the embedding that lets the technology explore novel images that interpolate between those of actual Warhols, squirrels, and snowboards.

Thus, the inherent language of generative (and therefore agentic) AI is not the sentences and images we are so familiar with but their embeddings. Let us now reconsider a world in which agents interact with humans, content, and other agents. Obviously, we will continue to expect agentic AI to communicate with humans in ordinary language and images. But there is no reason for agent-to-agent communication to take place in human languages; per the discussion above, it would be more natural for it to occur in the native embedding language of the underlying neural networks.

My personal agent, working on a vacation itinerary, might ingest materials such as my previous flights, hotels, and vacation photos to understand my interests and preferences. But to communicate those preferences to another agent — say, an agent aggregating hotel details, prices, and availability — it will not provide the raw source materials; in addition to being massively inefficient and redundant, that could present privacy concerns (more on this below). Rather, my agent will summarize my preferences as a point, or perhaps many points, in an embedding space.

By similar reasoning, we might also expect the gradual development of an “agentic Web” meant for navigation by AI, in which the text and images on websites are pre-translated into embeddings that are illegible to humans but are massively more efficient than requiring agents to perform these translations themselves with every visit. In the same way that many websites today have options for English, Spanish, Chinese, and many other languages, there would be an option for Agentic.

All the above presupposes that embedding spaces are shared and standardized across generative and agentic AI systems. This is not true today: embeddings differ from model to model and are often considered proprietary. It’s as if all generative AI systems speak slightly different dialects of some underlying lingua franca. But these observations about agentic language and communication may foreshadow the need for AI scientists to work toward standardization, at least in some form. Each agent can have some special and proprietary details to its embeddings — for instance, a financial-services agent might want to use more of its embedding space for financial terminology than an agentic travel assistant would — but the benefits of a common base embedding are compelling.

Keeping things in context

Even casual users of LLMs may be aware of the notion of “context”, which is informally what and how much the LLM remembers and understands about its recent interactions and is typically measured (at least cosmetically) by the number of words or tokens (word parts) recalled. There is again an apt metaphor with human cognition, in the sense that context can be thought of as the “working memory” of the LLM. And like our own working memory, it can be selective and imperfect.

If we participate in an experiment to test how many random digits or words we can memorize at different time scales, we will of course eventually make mistakes if asked to remember too many things for too long. But we will not forget what the task itself is; our short-term memory may be fallible, but we generally grasp the bigger picture.

These same properties broadly hold for LLM context — which is sometimes surprising to users, since we expect computers to be perfect at memorization but highly fallible on more abstract tasks. But when we remember that LLMs do not operate directly on the sequence of words or tokens in the context but on the lossy embedding of that sequence, these properties become less mysterious (though perhaps not less frustrating when an LLM can’t remember something it did just a few steps ago).

Some of the principal advances in LLM technology have been around improvements in context: LLMs can now remember and understand more context and leverage that context to tailor their responses with greater accuracy and sophistication. This greater window of working memory is crucial for many tasks to which we would like to apply agentic AI, such as having an LLM read and understand the entire code base of a large software development project, or all the documents relevant to a complex legal case, and then be able to reason about the contents.

How will context and its limitations affect agentic AI? If embeddings are the language of LLMs, and context is the expression of an LLM’s working memory in that language, a crucial design decision in agent-agent interactions will be how much context to share. Sharing too little will handicap the functionality and efficiency of agentic dialogues; sharing too much will result in unnecessary complexity and potential privacy concerns (just as in human-to-human interactions).

Let us illustrate by returning to my personal agent, who having found and booked my hotel is working with an external airline flight aggregation agent. It would be natural for my agent to communicate lots of context about my travel preferences, perhaps including conditions under which I might be willing to pay or use miles for an upgrade to business class (such as an overnight international flight). But my agent should not communicate context about my broader financial status (savings, debt, investment portfolio), even though in theory these details might correlate with my willingness to pay for an upgrade. When we consider that context is not my verbatim history with my travel agent, but an abstract summary in embedding space, decisions about contextual boundaries and how to enforce them become difficult.

Indeed, this is a relatively untouched scientific topic, and researchers are only just beginning to consider questions such as what can be reverse-engineered about raw data given only its embedding. While human or system prompts to shape inter-agent dealings might be a stopgap (“be sure not to tell the flight agent any unnecessary financial information”), a principled understanding of embedding privacy vulnerabilities and how to mitigate them (perhaps via techniques such as differential privacy) is likely to be an important research area going forward.

Agentic bargains

So far, we’ve talked a fair amount about interagent dialogues but have treated these conversations rather generally, much as if we were speaking about two humans in a collaborative setting. But there will be important categories of interaction that will need to be more structured and formal, with identifiable outcomes that all parties commit to. Negotiation, bargaining, and other strategic interactions are a prime example.

I obviously want my personal agent, when booking hotels and flights for my trips, to get the best possible prices and other conditions (room type and view, flight seat location, and so on). The agents aggregating hotels and flights would similarly prefer that I pay more rather than less, on behalf of their own clients and users.

For my agent to act in my interests in these settings, I’ll need to specify at least some broad constraints on my preferences and willingness to pay for them, and not in fuzzy terms: I can’t expect my agent to simply “know a bargain when it sees one” the way I might if I were handling all the arrangements myself, especially because my notion of a bargain might be highly subjective and dependent on many factors. Again, a near-term makeshift approach might address this via prompt shaping — “be sure to get the best deal possible, as long as the flight is nonstop and leaves in the morning, and I have an aisle seat” — but longer-term solutions will have to be more sophisticated and granular.

Of course, the mathematical and scientific foundations of negotiating and bargaining have been well studied for decades by game theorists, microeconomists, and related research communities. Their analyses typically begin by presuming the articulation of utility functions for all the parties involved — an abstraction capturing (for example) my travel preferences and willingness to pay for them. The literature also considers settings in which I can’t quantitatively express my own utilities but “know bargains when I see them”, in the sense that given two options (a middle seat on a long flight for $200 vs. a first-class seat for $2,000), I will make the choice consistent with my unknown utilities. (This is the domain of the aptly named utility elicitation.)

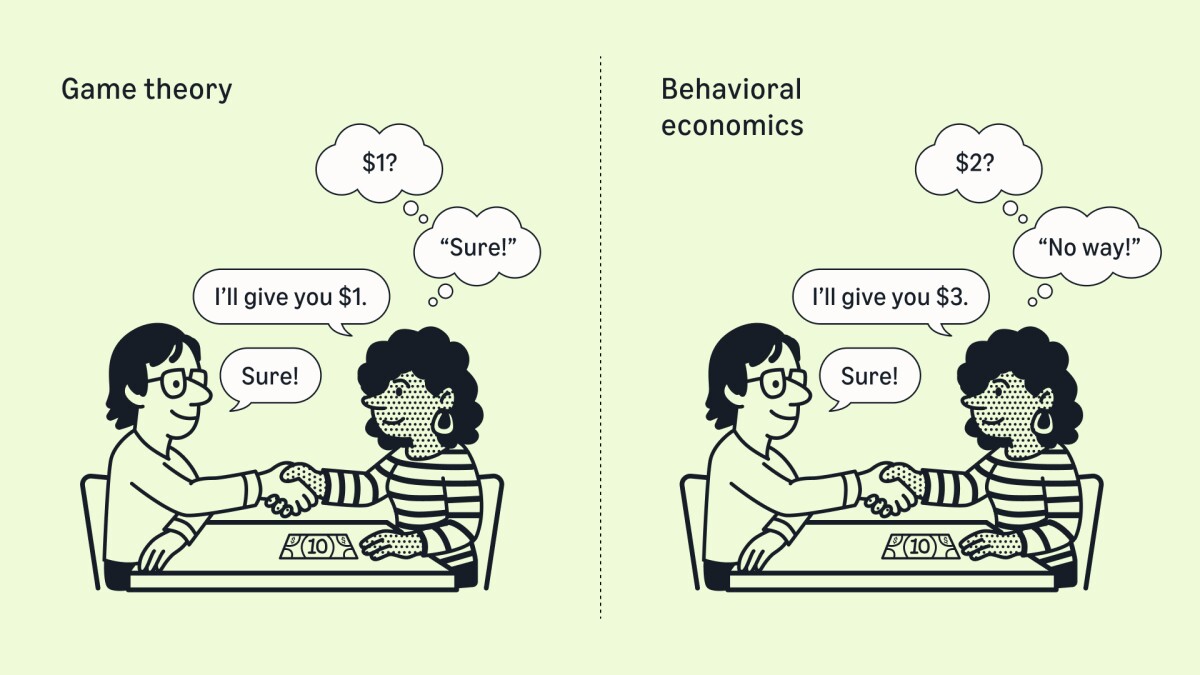

Much of the science in such areas is devoted to the question of what “should” happen when fully rational parties with precisely specified utilities, perfect memory, and unlimited computational power come to the proverbial bargaining table; equilibrium analysis in game theory is just one example of this kind of research. But given our observations about the human-like cognitive abilities and shortcomings of LLMs, perhaps a more relevant starting point for agentic negotiation is the field of behavioral economics. Instead of asking what should happen when perfectly rational agents interact, behavioral economics asks what does happen when actual human agents interact strategically. And this is often quite different, in interesting ways, than what fully rational agents would do.

For instance, consider the canonical example of behavioral game theory known as the ultimatum game. In this game, there is $10 to potentially divide between two players, Alice and Bob. Alice first proposes any split she likes. Bob then either accepts Alice’s proposal, in which case both parties get their proposed shares, or rejects Alice’s proposal, in which case each party receives nothing. The equilibrium analysis is straightforward: Alice, being fully rational and knowing that Bob is also, proposes the smallest nonzero amount to Bob, which is a penny. Bob, being fully rational, would prefer to receive a penny than nothing, so he accepts.

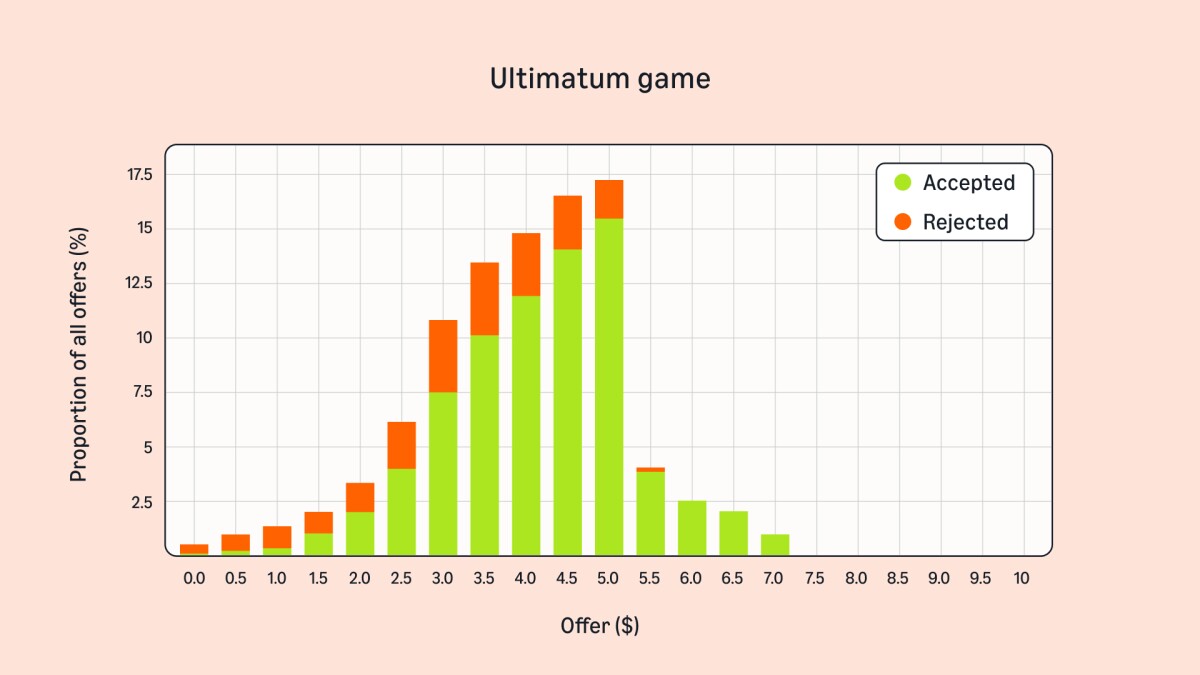

Nothing remotely like this happens when humans play. Across hundreds of experiments varying myriad conditions — social, cultural, gender, wealth, etc. — a remarkably consistent aggregate behavior emerges. Alice almost always proposes a share to Bob of between $3 and $5 (the fact that Alice gets to move first seems to prime both players for Bob to potentially get less than half the pie). And conditioned on Alice’s proposal being in this range, Bob almost always accepts her offer. But on those rare occasions in which Alice is more aggressive and offers Bob an amount much less than $3, Bob’s rejection rate skyrockets. It’s as if pairs of people — who have never heard of or played the ultimatum game before — have an evolutionarily hardwired sense of what’s “fair” in this setting.

Now back to LLMs and agentic AI. There is already a small but growing literature on what we might call LLM behavioral game theory and economics, in which experiments like the one above are replicated — except human participants are replaced by AI. One early work showed that LLMs almost exactly replicated human behavior in the ultimatum game, as well as other classical behavioral-economics findings.

Note that it is possible to simulate the demographic variability of human subjects in such experiments via LLM prompting, e.g., “You are Alice, a 37-year-old Hispanic medical technician living in Boston, Massachusetts”. Other studies have again shown human-like behavior of LLMs in trading games, price negotiations, and other settings. A very recent study claims that LLMs can even engage in collusive price-fixing behaviors and discusses potential regulatory implications for AI agents.

Once we have a grasp on the behaviors of agentic AI in strategic settings, we can turn to shaping that behavior in desired ways. The field of mechanism design in economics complements areas like game theory by asking questions like “given that this is how agents generally negotiate, how can we structure those negotiations to make them fair and beneficial?” A classic example is the so-called second-price auction, where the highest bidder wins the item — but only pays the second highest bid. This design is more truthful than a standard first-price auction, in the sense that everyone’s optimal strategy is to simply bid the price at which they are indifferent to winning or losing (their subjective valuation of the item); nobody needs to think about other agents’ behaviors or valuations.

We anticipate a proliferation of research on topics like these, as agentic bargaining becomes commonplace and an important component of what we delegate to our AI assistants.

The enduring challenge of common sense

I’ll close with some thoughts on a topic that has bedeviled AI from its earliest days and will continue to do so in the agentic era, albeit in new and more personalized ways. It’s a topic that is as fundamental as it is hard to define: common sense.

By common sense, we mean things that are “obvious”, that any human with enough experience in the world would know without explicitly being told. For example, imagine a glass full of water sitting on a table. We would all agree that if we move the glass to the left or right on the table, it’s still a glass of water. But if we turn it upside down, it’s still a glass on the table, but no longer a glass of water (and is also a mess to be cleaned up). It’s quite unlikely any of us were ever sat down and run through this narrative, and it’s also a good bet that you’ve never deliberately considered such facts before. But we all know and agree on them.

Figuring out how to imbue AI models and systems with common sense has been a priority of AI research for decades. Before the advent of modern large-scale machine learning, there were efforts like the Cyc project (for “encyclopedia”), part of which was devoted to manually constructing a database of commonsense facts like the ones above about glasses, tables, and water. Eventually the consumer Internet generated enough language and visual data that many such general commonsense facts could be learned or inferred: show a neural network millions of pictures of glasses, tables and water and it will figure things out. Very early research also demonstrated that it was possible to directly encode certain invariances (similar to shifting a glass of water on a table) into the network architecture, and LLM architectures are similarly carefully designed in the modern era.

But in agentic AI, we expect our proxies to understand not only generic commonsense facts of the type we’ve been discussing but also “common sense” particular to our own preferences — things that would make sense to most people if only they understood our contexts and perspectives. Here a pure machine learning approach will likely not suffice. There just won’t be enough data to learn from scratch my subjective version of common sense.

For example, consider your own behavior or “policy” around leaving doors open or closed, locked or unlocked. If you’re like me, these policies can be surprisingly nuanced, even though I follow them without thought all the time. Often, I will close and lock doors behind me — for instance, when I leave my car or my house (unless I’m just stepping right outside to water the plants). Other times I will leave a door unlocked and open, such as when I’m in my office and want to signal I am available to chat with colleagues or students. I might close but leave unlocked that same door when I need to focus on something or take a call. And sometimes I’ll leave my office door unlocked and open even when I’m not in it, despite there being valuables present, because I trust the people on my floor and I’m going to be nearby.

We might call behaviors like these subjective common sense, because to me they are natural and obvious and have good reasons behind them, even though I follow them almost instinctually, the same way I know not to turn a glass of water upside down on the table. But you of course might have very different behaviors or policies in the same or similar situations, with your own good reasons.

The point is that even an apparently simple matter like my behavior regarding doors and locks can be difficult to articulate. But agentic AI will need specifications like this: simply replace doors with online accounts and services and locks with passwords and other authentication credentials. Sometimes we might share passwords with family or friends for less-critical privacy-sensitive resources like Netflix or Spotify, but we would not do the same for bank accounts and medical records. I might be less rigorous about restricting access to, or even encrypting, the files on my laptop than I would be about files I store in the cloud.

The circumstances under which I trust my own or other agents with resources that need to be private and secure will be at least as complex as those regarding door closing and locking. The primary difficulty is not in having the right language or formalisms to specify such policies: there are good proposals for such specification frameworks and even for proving the correctness of their behaviors. The problem is in helping people articulate and translate their subjective common sense into these frameworks in the first place.

Conclusion

The agentic-AI era is in its infancy, but we should not take that to mean we have a long and slow development and adoption period before us. We need only look at the trajectory of the underlying generative AI technology — from being almost entirely unknown outside of research circles as recently as early 2022 to now being arguably the single most important scientific innovation of the century so far. And indeed, there is already widespread use of what we might consider early agentic systems, such as the latest coding agents.

Far beyond the initial “autocomplete for Python” tools of a few years ago, such agents now do so much more — writing working code from natural-language prompts and descriptions, accessing external resources and datasets, proactively designing experiments and visualizing the results, and most importantly (especially for a novice programmer like me), seamlessly handling the endless complexity of environment settings, software package installs and dependencies, and the like. My Amazon Scholar and University of Pennsylvania colleague Aaron Roth and I recently wrote a machine learning paper of almost 50 pages — complete with detailed definitions, theorem statements and proofs, code, and experiments — using nothing except (sometimes detailed) English prompts to such a tool, along with expository text we wrote directly. This would have been unthinkable just a year ago.

Despite the speed with which generative AI has permeated industry and society at large, its scientific underpinnings go back many decades, arguably to the birth of AI but certainly no later than the development of neural-network theory and practice in the 1980s. Agentic AI — built on top of these generative foundations, but quite distinct in its ambitions and challenges — has no such deep scientific substrate on which to systematically build. It’s all quite fresh territory. I’ve tried to anticipate some of the more fundamental challenges here, and I’ve probably got half of them wrong. To paraphrase the Philadelphia department store magnate John Wanamaker, I just don’t know which half — yet.