Today, using drones in responding to natural or man-made disasters is limited by the fact that they need to be both individually piloted and have their observations interpreted by a human. But what if drones could “see” on their own? What if they could not only make decisions about navigation, but also where to look more closely — or even collaborate with other drones and robots to observe a specific location?

So great to be out testing with the V4RL team again! Here's a sneaky peak of our autonomous VI planner selecting the next best viewpoint live,to appear in RAL/IROS 2021. Kudos @yveskompis, Luca Bartolomei, Marco Karrer, and Thomas Ziegler!

— Margarita Chli (@MargaritaChli) July 8, 2021

#roboticsainews @ETH_en #VaccinesWork pic.twitter.com/uZiWZKNlwf

That suite of skills is exactly what Margarita Chli, an Amazon Research Award recipient and vice director at the Institute of Robotics and Intelligent Systems at ETH Zurich (the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), is exploring. Chli heads up the Vision for Robotics Lab there (V4RL), and she’s been using her 2019 Amazon Research Award (she was awarded one in 2020 as well) to advance robotic vision for small aircraft, including drones.

Chli grew up in Greece and Cyprus with math teachers as parents, so while she was “heavily trained” in the language of mathematics, she didn’t always know robotics would be her professional focus.

Chli says it was really a series of lucky events that led to her introduction to “influential and brilliant scientists who planted the seed of intellectual curiosity in this area.”

After studying computer science and engineering at the University of Cambridge, where she earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, she considered her options.

“The coolest thing at the time seemed to be this PhD position at Imperial College in London, where my advisor, Andrew Davison, brought me into the area of robotic vision. That’s how it all started,” says Chli.

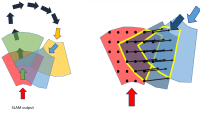

Davison’s expertise was pioneering monocular SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping), which is about “understanding how a camera moves in space,” says Chli. In pursuing her PhD, Chli did a lot of coding on her laptop, connecting that computer to a single camera and testing algorithms.

During her postdoc at ETH Zurich, which began in 2010, she applied her computer-vision algorithms to small drones. Chli says it was exciting to translate what she was doing on her laptop to a robot that was actually moving. That’s when she envisioned the potential impact for this technology.

“It's one thing to write some code and look at beautiful images, and another thing to get a robot moving – you get a feeling that you're creating something. And even going beyond that, to create something that can help people,” says Chli.

Drones in disaster zones

Her time at ETH Zurich also marked an era where drones, which had once been prohibitively expensive, were becoming more popular and accessible. “The technological hardware side of things was blooming, which meant we could run then-expensive image-processing algorithms onboard smaller and smaller platforms.” Those drones were more expensive, bulkier, less flexible, and lacked the processing power compared to today’s drones, “but nevertheless, the applications and imagination were there already,” she says.

As she wrote her research proposals, Chli expanded her thinking about the power of this technology. “What can we do with this? How we can use drones and robots and robotic vision to have robots in our everyday lives, that that can help us with tasks that we don't want to do?”

Those questions have propelled her research ever since.

One of the first projects Chli got to work on at ETH Zurich — where she was appointed as a deputy director of the lab she was working as a postdoc — was using drones for search-and-rescue missions. That work involved drones accessing areas that would be too dangerous or time-consuming for rescuers on foot, allowing rescuers to search for missing people with less risk.

Working backwards from the end-user, Chli spoke with rescuers at Club Alpino Italiano and learned that they didn’t want anything in the field that wasn’t directly useful — drones that worked independently made more sense than dedicating human resources to flying and monitoring drones.

These rescuers had lost colleagues to this very risky work, which takes place in harsh weather conditions, and so they were understandably demanding — and skeptical. “They had no time for delays or mistakes from fussy hardware or software,” she says.

The requirement for simplicity and a just-works solution has “been a great drive for my research ever since, to be honest: to develop plug-and-play, no-fuss systems, such that mission experts do not need to also be robotics experts or pilots.”

While supporting the work of search-and-rescue teams is still an important component of her work, Chli and team have expanded the scope of their research.

Chli also envisions drones being used for inspecting hard-to-reach areas like wind-turbine blades, or power plants. “In 2012, there was a big explosion in the power plant on the island where I come from in Cyprus. We needed drones to be able to inspect the boilers for cracks to figure out how safe it was for humans to go closer,” she says.

Truly useful robots

This incident inspired Chli to focus on designing robots with real utility.

“I found it quite astonishing that we would see in the news robots that could do all sorts of gimmicky things, but we didn’t have reliable enough robots that could really help humans in a time of dire need.” She wanted to change that, and with her background in robotic vision and interest in drones, creating an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that could “see” was the next challenge. In 2013, she was part of the team that ran the first vision-based autonomous flights of a small helicopter.

That same year, Chli took a post as a professor at the University of Edinburgh as a Chancellor's fellow. There, she started Vision for Robotics Lab (V4RL), which focuses on vision for robots, especially UAVs. In 2015, she returned to ETH Zurich, where she’s now professor and continues to lead V4RL.

Her research has been accelerated thanks to the resources made available to her as an Amazon Research Award recipient; resources that include access to AWS EC2 and S3.

“I think that what Amazon is doing is a great thing, because it's helping us actually see what researchers can do with its tools and it is democratizing where research is going,” she says.

She’s using those tools to tackle some of the most important problems in her work at ETH Zurich, like “how to figure out where a good spot to land is for our drones, and how we can keep a drone estimating its motion as accurately as possible, without being affected by water, trees, pedestrians, cars, and other dynamic, moving parts of the scene.” While flight-critical tasks must be processed on the drones themselves, transferring other processing tasks to the cloud, like semantic segmentation and high-level path planning, makes sense, says Chli.

Drones helping humanity

Chli thinks drones that can see and make decisions on their own will serve humanity outside search-and-rescue operations.

Researchers tracking wildlife migrations or large, dispersed herds could use drones to keep tabs on individual animals in ways humans on foot can’t, while at the same time understanding group movements.

Robots are going to help us in many ways that today we cannot really imagine, in ways we never thought possible.

“Archaeologists have come to us and said, ‘We have about 250 archaeological sites in Greece, we have a few tools around like a tripod, and I can put it in different places and take laser scans, but it's heavy, it's bulky. I don't want to find holes in my model, because I don't have time to go back to every one of these sites to capture new data.’ That’s where drones could be ideal, because they can map an area,” says Chli.

Chli says she’s become a bit of a drone evangelist because often when people hear her speak about autonomous drones, they think of military applications — whereas her focus is on what robots can do to improve the human condition.

Chli said she understands how that distrust emerged. “This technology has been growing very quickly, particularly comparing the progress today to a few years back,” she said. “And the less we know about how this technology works, the more scared we are of it.”

That’s why, she says, it’s important to raise questions and have open dialogues to address concerns because, as she sees it, robots are going to be part of our everyday lives.

“Robots are going to help us in many ways that today we cannot really imagine,” Chli says, “in ways we never thought possible.”