Editor’s note: Mina Ghashami is an applied scientist in Alexa Video and an adjunct lecturer at Stanford University. Here she writes about how her experience as a teacher and teaching assistant has informed her work as a scientist.

As we at Amazon strive to be the most customer-centric company in the world, scientific innovation and improving the day-to-day lives of customers are at the heart of our principles. One way we keep the bar for scientific innovation high is through collaboration with bright minds from academic institutes.

Academia and industry complement each other. They are, to an extent, separated by the process of translating research discoveries into applied research followed by development and commercialization. We need universities as they are at the frontier of science, introducing cutting-edge research. We also need industry as it gives back to academia in various ways. For example, industry demand for everything from scalability to millions of users, to low latency of real-time responses shapes the next generation of academic research.

Since I joined Amazon in 2020, I have had the opportunity to work with a diverse team of scientists, engineers, and product managers who helped me grow technically, become a more effective communicator, and expand my point of view by looking at problems from customers’ perspectives. As a scientist, one way for me to give back to academia is to teach.

Reflecting on my teaching experiences throughout years, I see that they have helped me to become a more well-rounded scientist. They have deepened my understanding of the subjects I’ve taught, mostly data mining and machine learning — topics which I heavily use in my day-to-day job as an applied scientist.

Learning from teaching

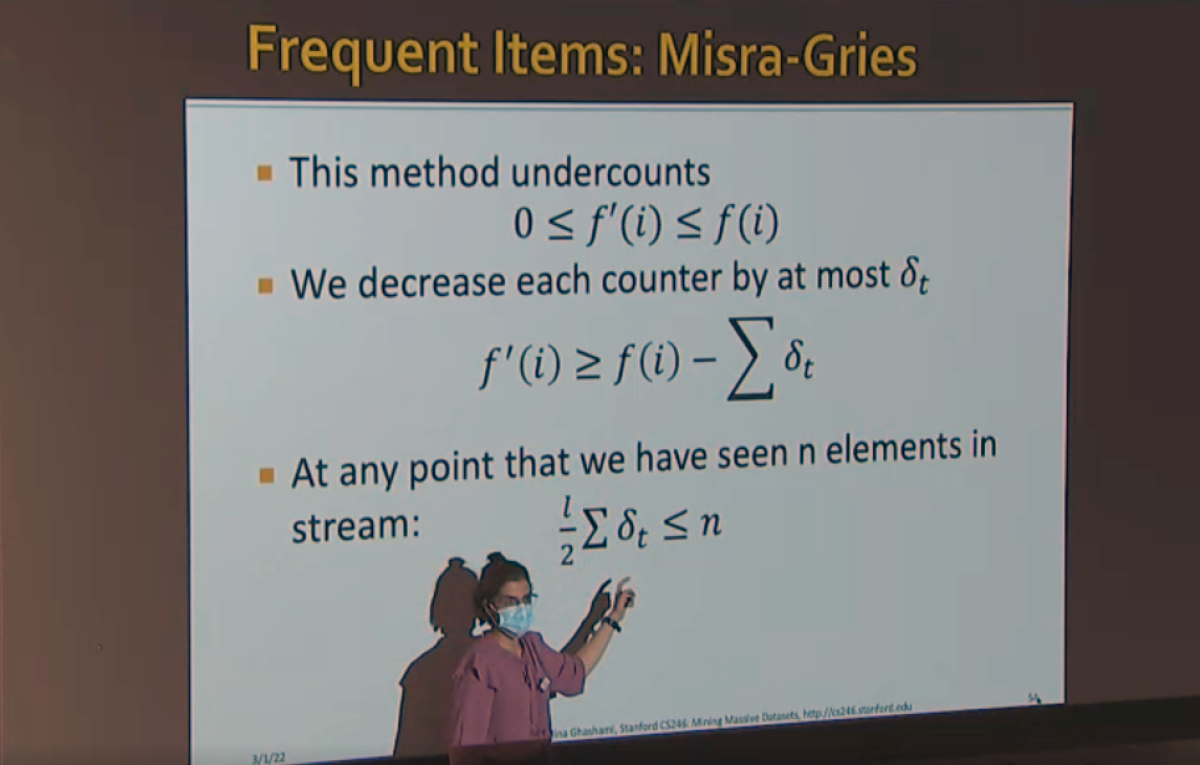

For example, in the first quarter of 2022, I had the pleasure of collaborating with Stanford University on a teaching opportunity as an adjunct lecturer. I was co-teaching the course, Mining Massive Data Sets with Jure Leskovec, which covers a mix of topics from large scale data mining and machine learning.

In one of the courses that I taught, we spent few sessions discussing state of the art recommendation algorithms and how they compare, how widely they are used in industrial use cases and related topics. Going through this comprehensive review taught me many details and nuances about which approaches work and which might not.

In that same quarter at Amazon, I was working on related problem in recommendation domain, and knowing the various already tried flavors of recommenders equipped me with an insight that helped to approach the problem in a more well-versed manner.

A rewarding endeavor

In addition to the opportunity to learn, teaching is fun and rewarding. It calls upon your creativity to come up with new approaches, and mechanisms to make a subject as intuitive as possible without losing its essence. In my experience, classrooms have always been an interactive medium for learning.

Discussion-like theses in specialized graduate courses encourage free-form thinking, brainstorming, conceptualizing ideas and eventually may lead to concrete research ideas and artifacts — the very essence of collaboration.

Throughout my years in academia, I’ve taught both graduate and undergraduate level courses. Different level courses contribute differently to everyone’s (both students and teacher) knowledge.

In my PhD years at University of Utah, I taught a graduate-level seminar on matrix sketching which was centered on a research domain and discussed within a series of papers. As this class was designed to be an upper-level graduate course, we offered a comprehensive review of the literature around the matrix sketching field.

By the end of the course, not only were the students up to the date with the state of the art, but a couple of paper collaborations arose from the discussions in class.

Discussion-like theses in specialized graduate courses encourage free-form thinking, brainstorming, conceptualizing ideas and eventually may lead to concrete research ideas and artifacts — the very essence of collaboration.

On the other side of the spectrum, undergraduate courses provide a breadth of knowledge of the subject and help us to freshen up on fundamentals. During my postdoc time at Rutgers University, I taught a Design and Analysis of Data Structures and Algorithms course and it refreshed me on mathematical mechanisms and proofs underlying many computer science algorithms that we use from highly optimized libraries.

Providing a service

Teaching is also a service we provide to the community, an opportunity to pay it forward for all it has taught us. Through years in academia, I’ve had the privilege to work with some outstanding researchers and professors who inspired me to articulate subjects with intuition.

One included Suresh Venkatasubramanian, who I interacted with at the University of Utah and who is now a professor at computer science and data science department of Brown University. He was a natural in explicating complex theoretical fundamentals such as information theory.

Another mentor and co-author of mine was Edo Liberty, the CEO of Pinecone, who spent nearly three years at AWS as senior manager and then director of research. He was expert at making deceptively simple presentation slides, with a focus on key ideas and shaving off details.

These interactions taught me the value of building intuition both in problem solving and in teaching, as well as keeping it at right level to not confuse audiences. Nowadays when I teach, I try to make the ideas as tangible as possible and let math follow next to prove the intuition.

As a scientist, I am constantly working to expand my knowledge and understanding in order to ensure I can help deliver outcomes that improve the customer experience. As a teacher, I understand how important it is to share knowledge in accessible ways and how the act of teaching can further my own understanding and help me to be a better scientist.

I encourage my fellow scientists to try to make the time to teach if you can — it just might make you a more well-rounded scientist.